- Turkey is dependent on oil and natural gas imports to fuel the country’s economic growth

- Turkey has scored major success with string of energy agreements with the KRG

- Turkey, led by Recep Erdogan, is now mired in a complex and volatile situation at its borders

- Initial improvements in relations with Turkey’s Kurdish minority now in question

- Currently benefiting from both low oil market prices and cheap clandestine imports from ISIS-held Syrian oil fields but energy partnership is a “gas play” for Ankara.

INTRODUCTION

Recep Erdogan, Turkey’s President, and Ahmet Davutoglu, who recently became Turkey’s prime minister after serving for years as foreign minister, have been playing an astute game since 2012, despite having to break away from their “zero problems with neighbors” policy.

Ankara has safeguarded Turkey’s economic growth potential by securing long-term energy supplies from Iraqi Kurdistan while offering Turkish Kurds the prospects of a normalization in relations.

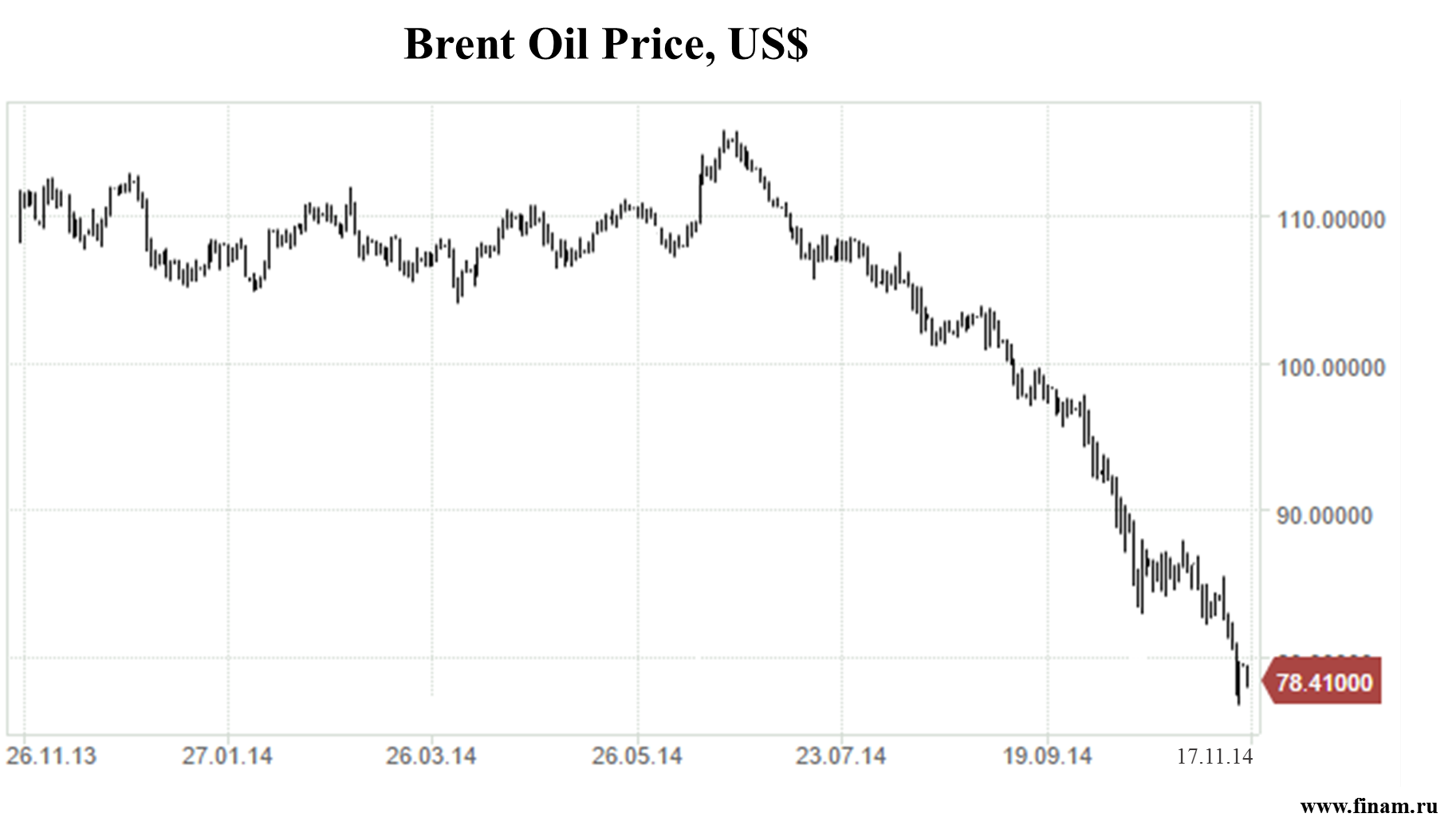

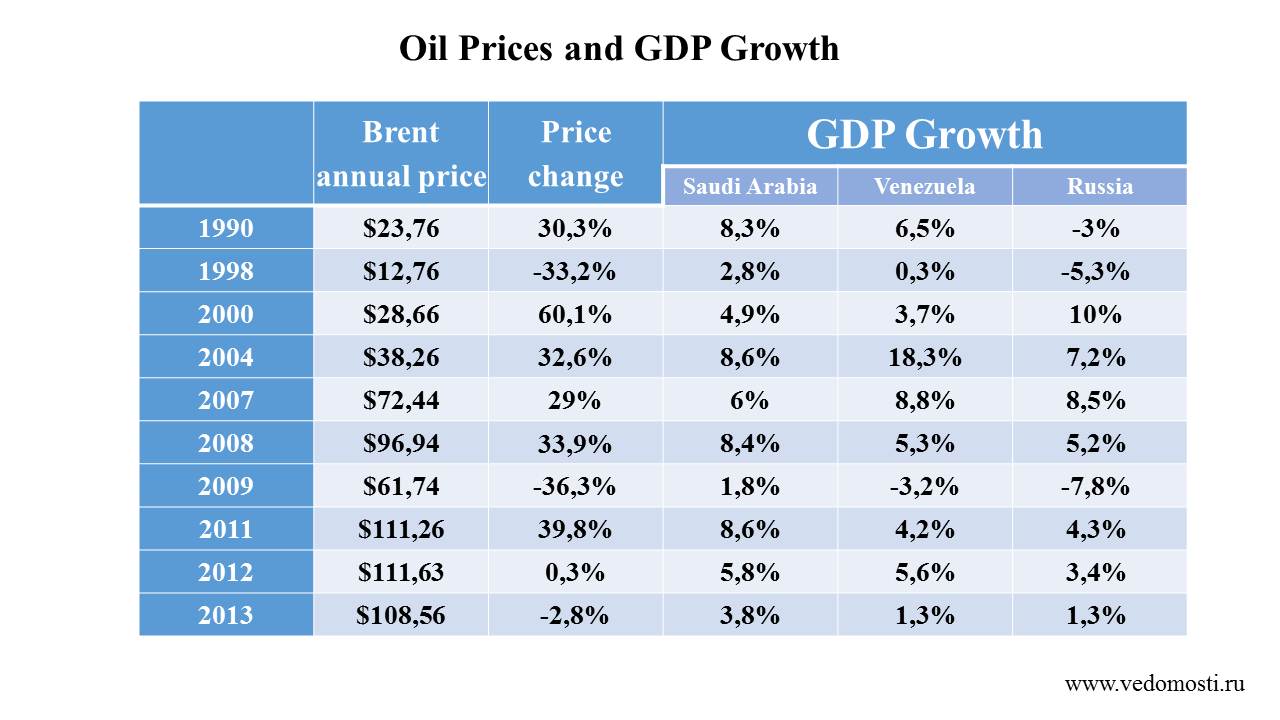

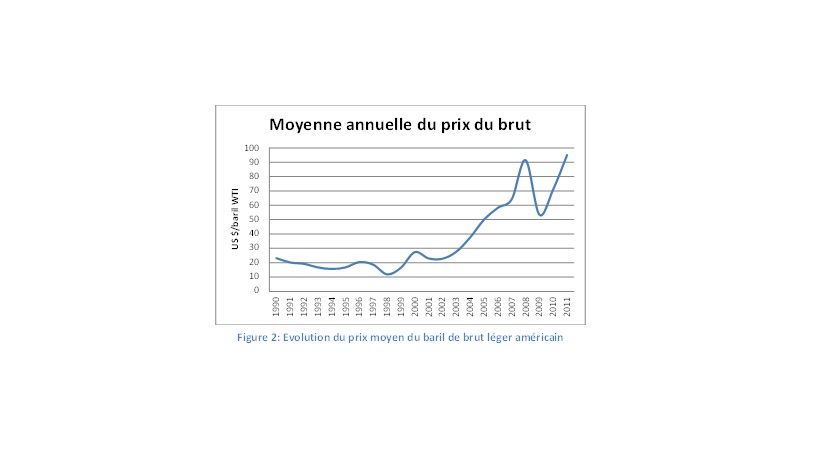

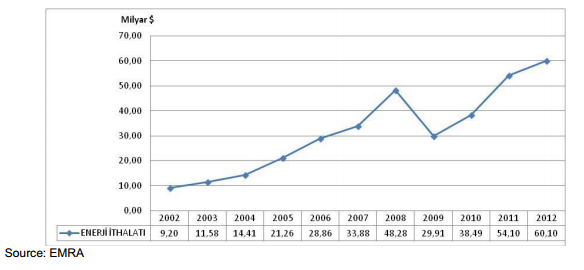

The importance of the energy deals with the KRG must also be seen in light of Turkey’s large account deficit. Turkey really felt the pinch in 2013 when oil prices surged above 115 USD per barrel. The rise in oil prices in August 2013 alone imposed an additional financial burden of around $300 million on Turkey.

The recent plight of Syrian Kurds on Turkey’s very doorstep, however, has thrown a more cynical light on Recep Erdogan’s regional strategy. Ankara is now playing a cautious game on three fronts:

- Securing domestic stability in light of Turkish Kurdish emotions and Islamist extremists on its own territory

- Safeguarding Turkey’s growth prospects thanks to energy agreements with the KRG

- Maintaining territorial integrity despite calls for a break-up of Syria

THE CREATION OF A NEW REGIONAL ENERGY NEXUS

Turkey’s thirst for energy

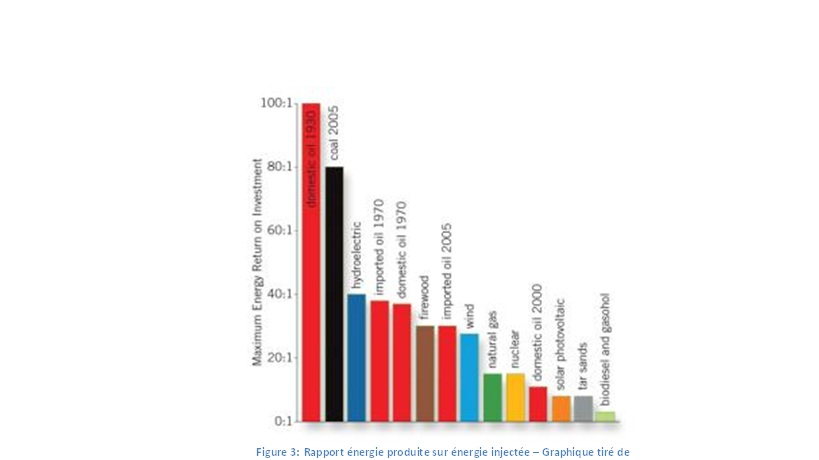

A Booming economy reliant on foreign energy

Since 2005, the Turkish economy has growth from 392.2 Billion USD to a projected 820.21 billion USD in 2014, despite the marked dip in 2009 following the US subprime crisis.

After experiencing years of continuous economic growth, Turkey’s economy started slowing down in 2013. In 2014, the government came under intense market pressure to take action and prove sluggish 2015 growth outlooks wrong, while the large current account deficit has become a major political issue.

Electricity production

Turkey’s electricity demand grew by more than 90% from 2001 to 2011. In 2012, Turkey’s total electricity generating capacity was 56.1 GWe and total net electricity generation was 228 TWhe.

Production is split between natural gas, coal and hydro. Fossil fuel sources account for the largest share of electricity generation, with natural gas as the most important source (47%).

Due to the large number of on-site power production plants running on natural gas at industrial and commercial sites, autoproducers are important electricity market actors, with an increasing market share.

According to « Turkish Electrical Energy 10 Year Generation Capacity Projection (2010-2019) », prepared by the Turkish Electricity Transmission Corporation (TEIAS), expected yearly average demand growth rates are expected to be between 6,5% and 7,5%. The report foresees that electricity consumption shall reach 390 TWh by 2019 in case of high demand against 367 TWh in the low demand scenario. In both cases, Turkey will be facing electricity shortage in 2016.

Turkey has been looking for diversify its electricity production mix but renewable energy generation is only starting to gain real traction. Turkey has a large wind potential and the Turkish Ministry hopes to grow a limited capacity base to 10,000 MW in 2015 and 20,000 MW in 2023, playing a major role in achieving the stated 30% renewable electricity target for 2010 set by the government.

Currently however, alternatives to natural gas power production prove more capital intensive, with investment horizons well beyond the 3 year mark required by most Turkish investors in uncertain times.

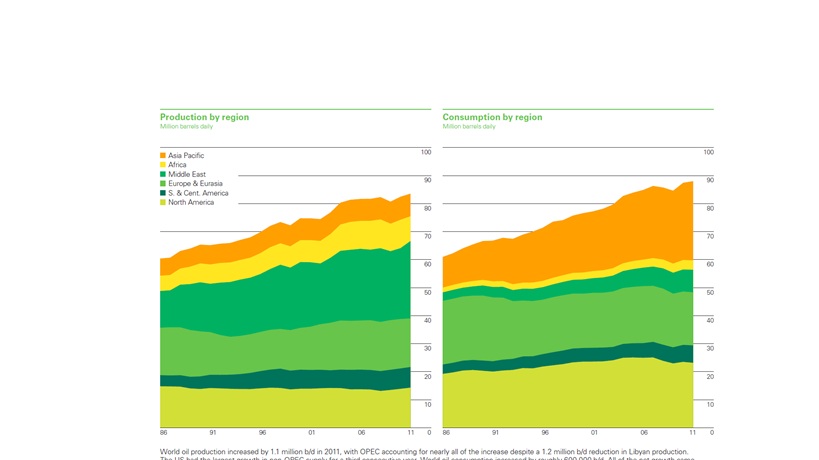

Oil

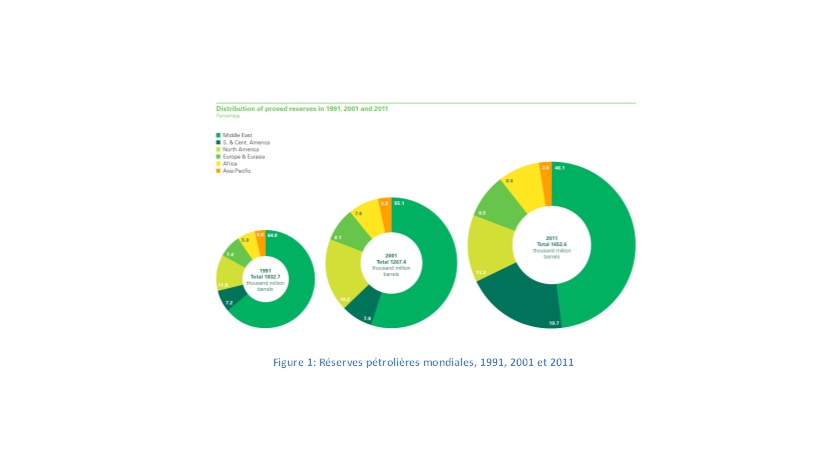

According to the US Energy Information Agency, Turkey’s total liquid fuels consumption averaged 734,800 bbl/d in 2013, with more than 90% of crude oil consumption being imported. In 2012, Iran accounted for 35% of the country’s supply.

In 2010, around 50% of Turkish total oil demand was consumed in the transport sector, while the industry sector and the commercial/agriculture/other sector accounted for 24% and 14% respectively. Relatively high oil demand in the industry sector derives from the construction and chemical sectors (33 % and 31% of industry’s share, respectively).

Crucially, the IEA expects Turkey’s crude oil imports to double over the next decade. Turkey’s economy grew by 4% over 2013, and total consumption of liquid fuels in Turkey increased by another 6% in that year.

Natural gas

While oil is an important fuel, particularly for transportation, natural gas has been powering Turkey’s economic development. The transformation sector has been the largest consumer of natural gas, representing about 48% of the country’s total gas consumption in 2011. Industrial growth will continue to spur demand for natural gas.

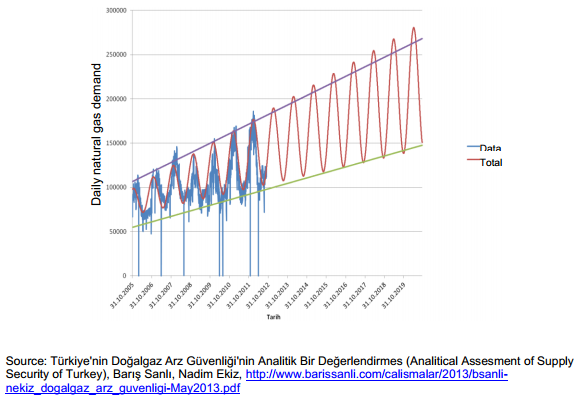

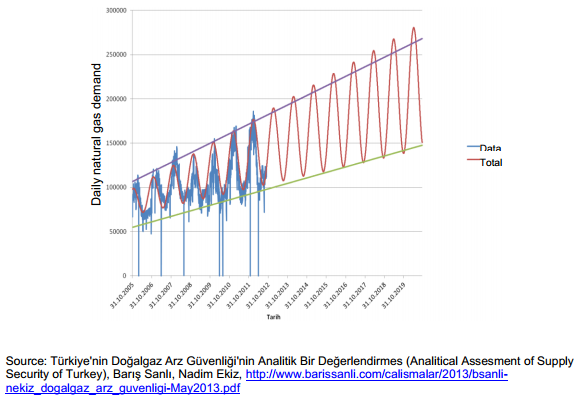

Turkey has struggled in recent years with seasonal demand variations. Peak demand in winter months can be twice the volumes consumed in summer months. The main sectors driving increases in winter natural gas demand are the electricity sector and residential sector, while the gap between summer and winter peak demand is expected to widen until 2019. By the winter of 2019, peak natural gas consumption is set to top 250 mcm/d, about 90 mcm/d above today’s level.

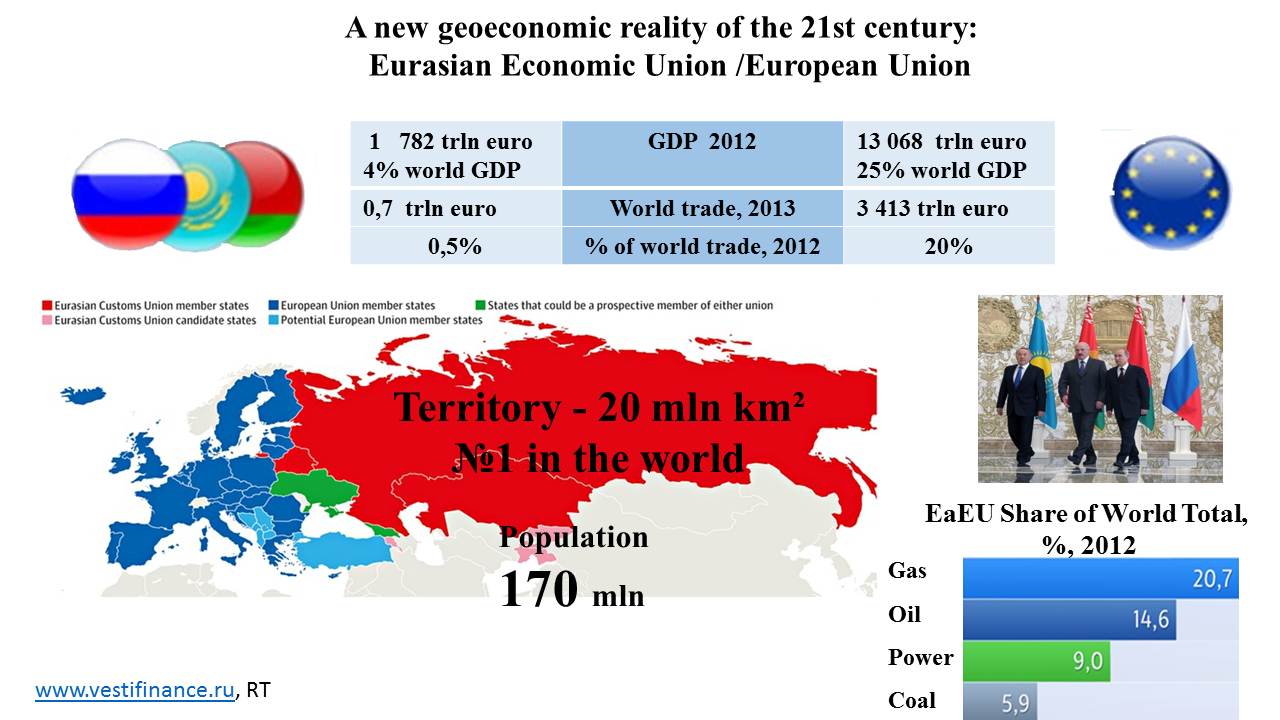

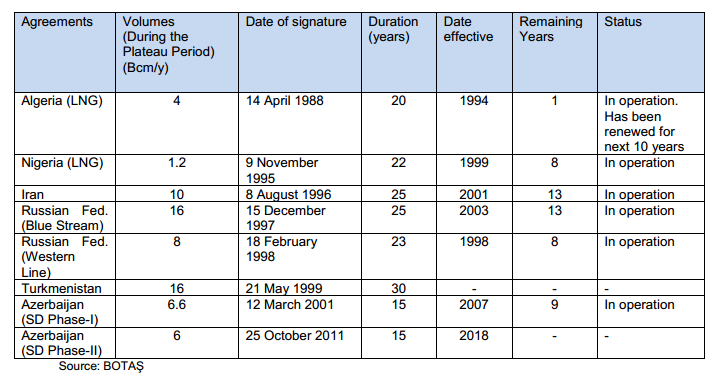

The IEA’s 2013 Turkey update noted that Turkish gas demand significantly increased from 0.7 billion cubic meters in 1987 to 45.3 bcm in 2012, while domestic production barely reached 0.6 bcm that year.

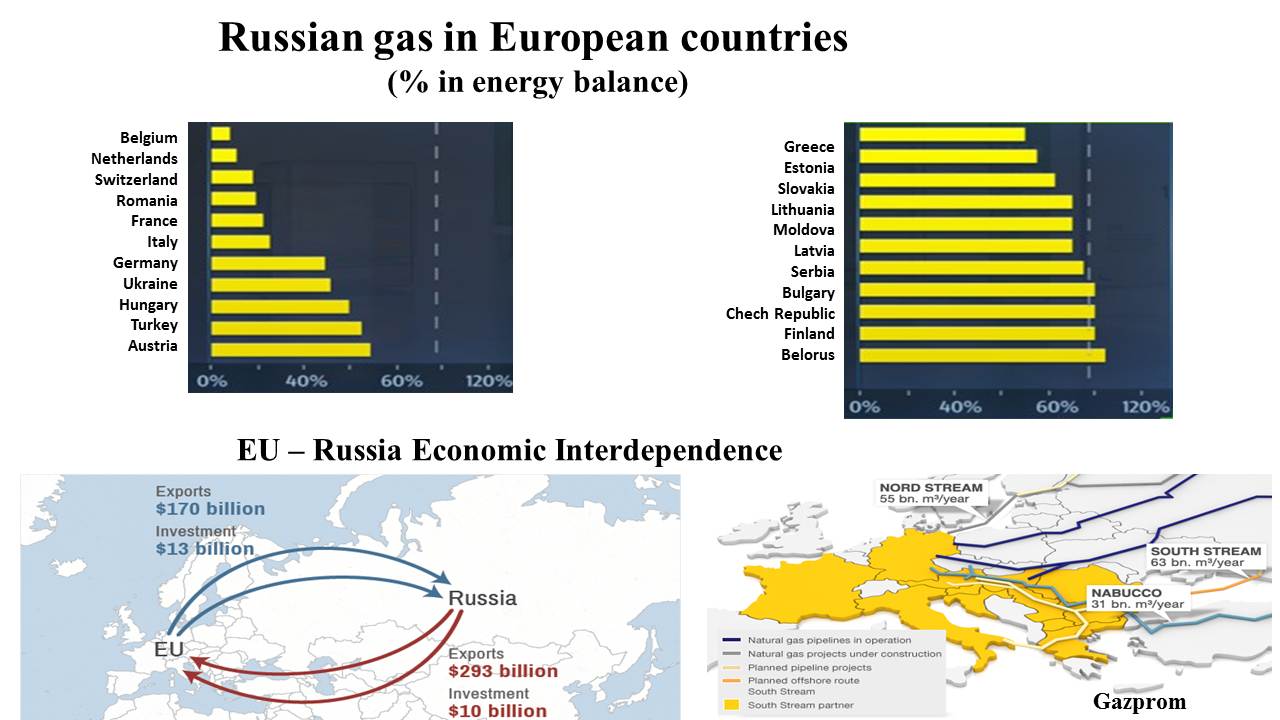

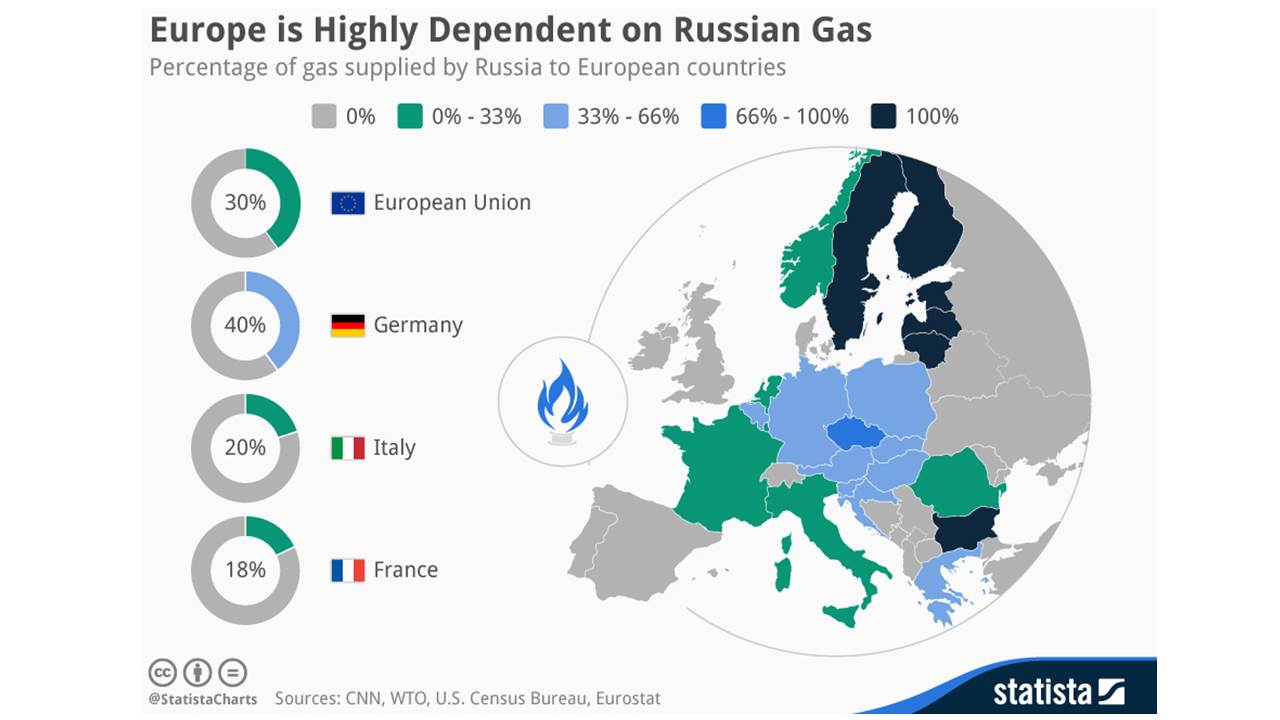

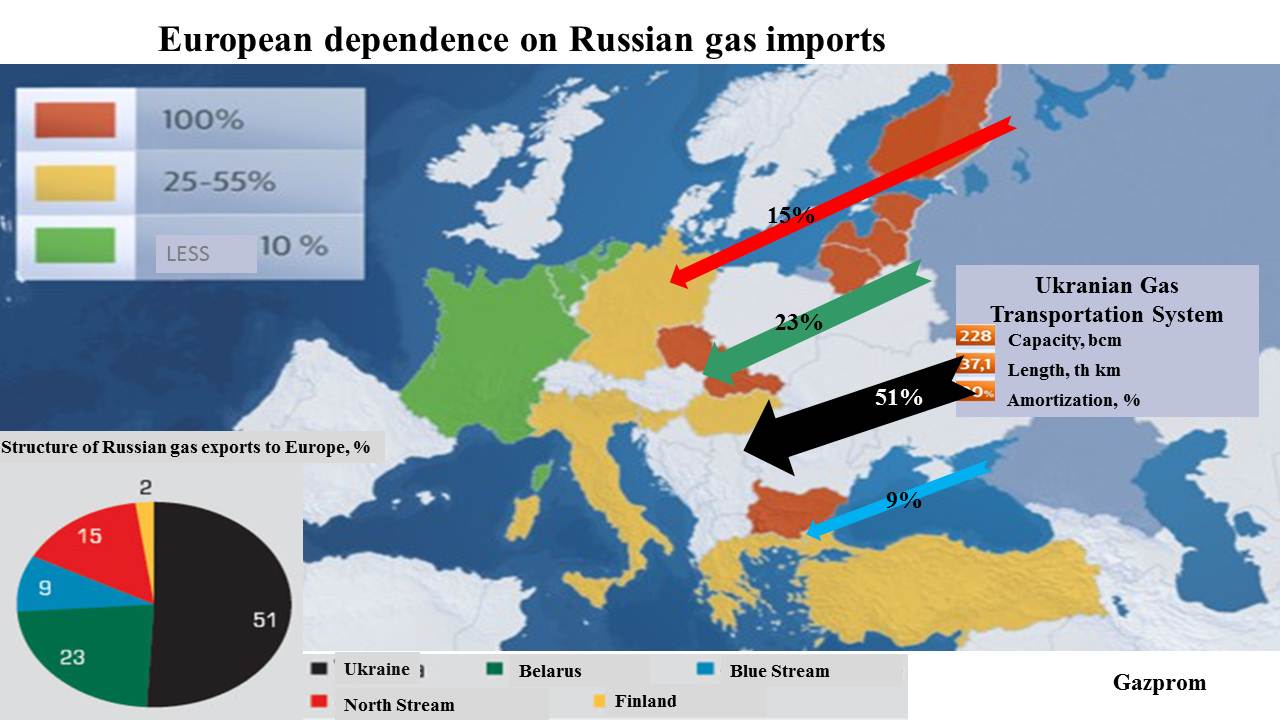

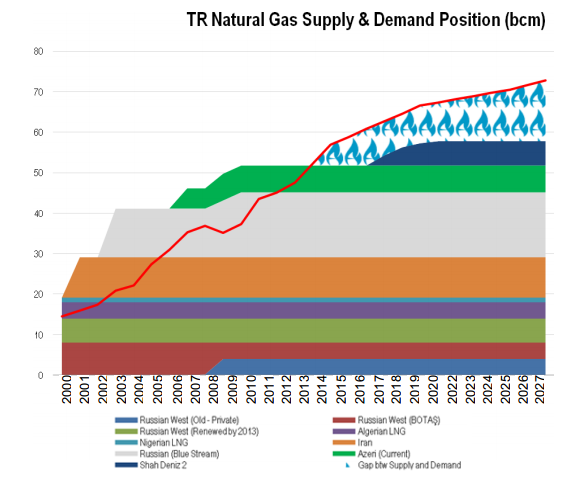

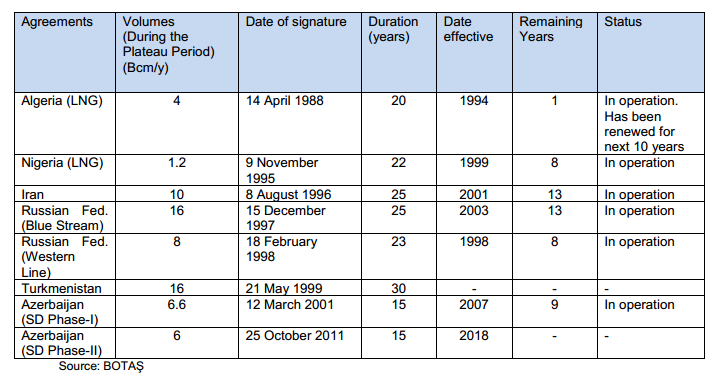

The country relies very heavily on natural gas imports. As of 2011, Russia alone accounted for 58% of Turkey’s gas imports.

Energy infrastructure has been a major focus of government policy and Turkey has planned to diversify natural gas import pathways through constructing new major cross border pipelines and LNG terminals, on top of the country’s four existing international pipelines with a total import capacity of some 46.6 bcm.

Imports from Azerbaijan, although much better value, also remain constrained by pipeline capacity. Even when the Trans-Anatolian Pipeline comes on-stream in about 2018, it will only provide Turkey with another 6bcm in the initial phase, not much – especially given the rapid increase of domestic gas demand. Azerbaijani gas is welcome but can only ever fulfil a small fraction of Turkey’s requirements. Yıldız’s claim that TANAP will cut domestic gas prices seems therefore optimistic.

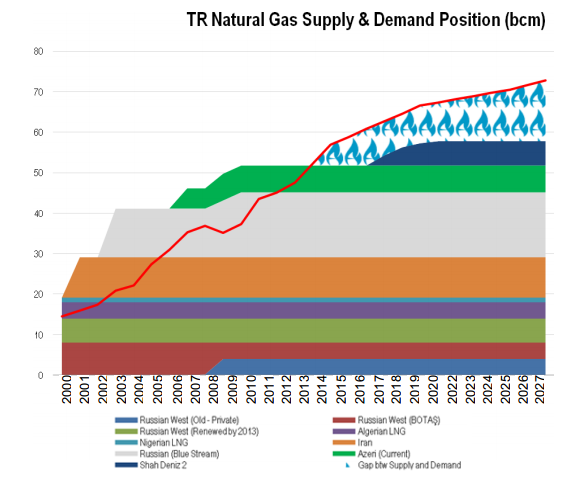

Turkey’s supply and demand position, based on Botas projections (but excluding spot LNG supplies), shows that Turkey could have a 5 Bcm annual supply deficit by 2015, despite having already renewed its LNG import with Algeria’s Sonatrach. By 2017, Turkey will need to import an additional 10 Bcm/y.

With the current natural gas supply network nearing full capacity, security of supply is already a major issue in Turkey and current policy aims at increasing natural gas storage facilities and power plants often have to be fitted with fuel switching capacity and hold sufficient amounts of secondary fuel such as diesel.

Source: Botas (in Natural Gas in the Turkish Domestic Enegry Market, Oxford Energy Research Institute, February 2014).

Looking at future trends, several contracts will be up for renewable as from 2021, as for example the 10 Bcm/y of Russian gas supplied through the Western Line to private companies.

Azerbaijan gas came at the lowest prices for natural gas, charging 349 USD/thousand cubic meter in 2013, compared to 428 USD for Russia gas and 507 USD for Iranian imports. Unfortunately for Turkey, new gas fields are only expected to come on line in Azerbaijan in 2025.

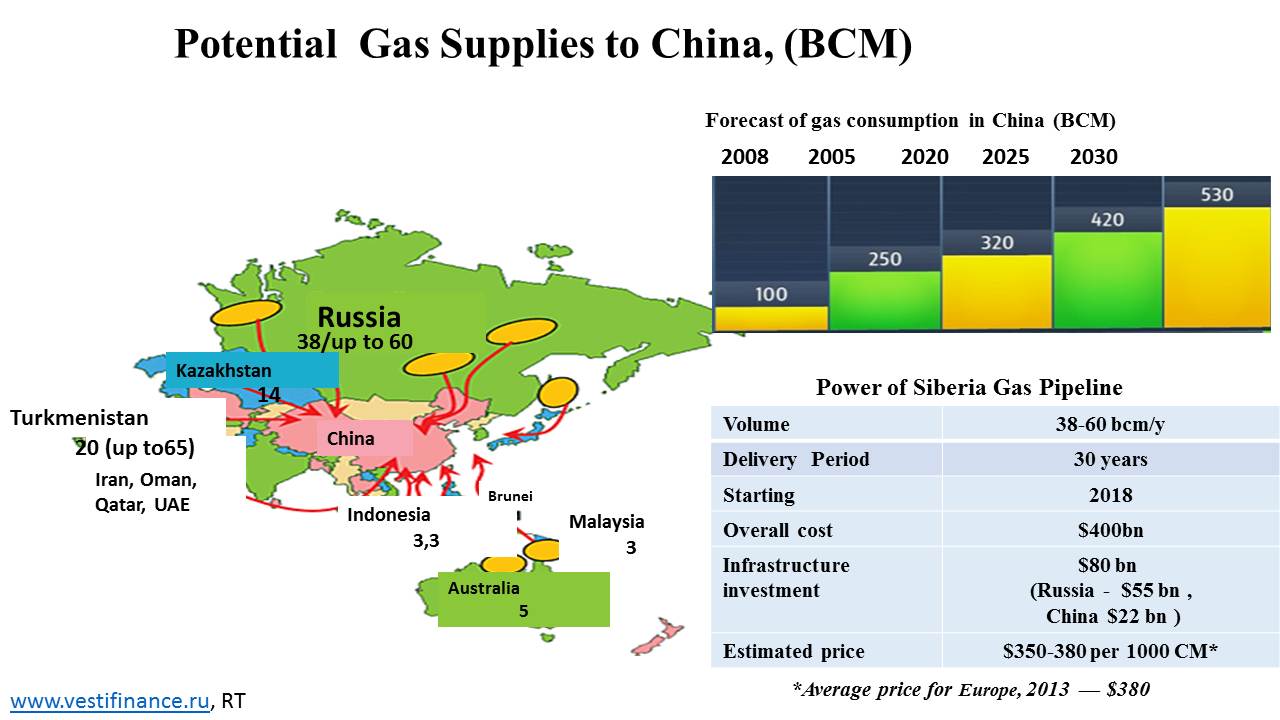

Turkey’s natural gas demand at the year 2030 was calculated as 76.8-83.8 bcm based on linear and logistic models, respectively. The most conservative scenarios (excluding nuclear power) table on demand reaching 70 Bcm/y in 2030. Household demand is expected to grow to 22.7 Bcm, up from 9 bcm/y and industry could go from 8 to 14 bcm. The main driver will be the projected 7% annual rise in electricity demand.

In this context the role KRG natural gas imports could play becomes plain to see.

The current figure of 46.6 bcm of natural gas import capacity must be compared with the projected additional import capacity from the KRG that should reach 10 bcm per year in the next few years, while Genel Energy Chairman Mehmet Sepil suggested recently that in ten years’ time tis figure could be as high as 30 bcm per year.

Needless to say, Turkey is having to balance its appetite for Iraqi Kurdish energy with the prospects of deteriorated relations with Baghdad.

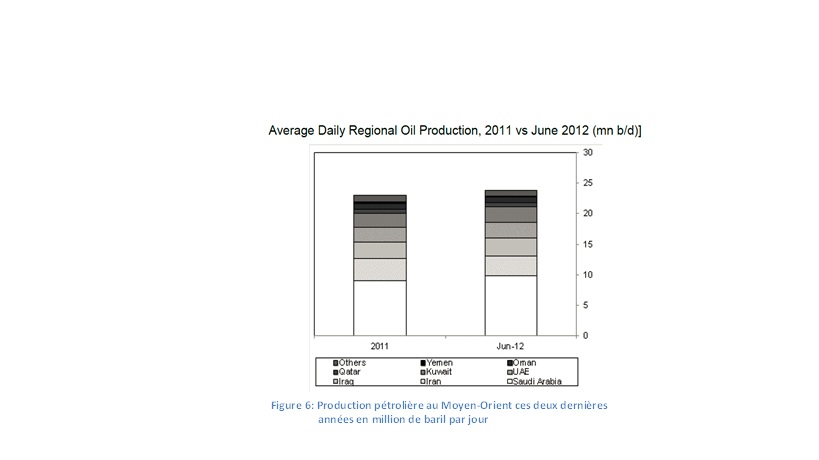

Iraqi Kurdistan, the new hydrocarbons frontier

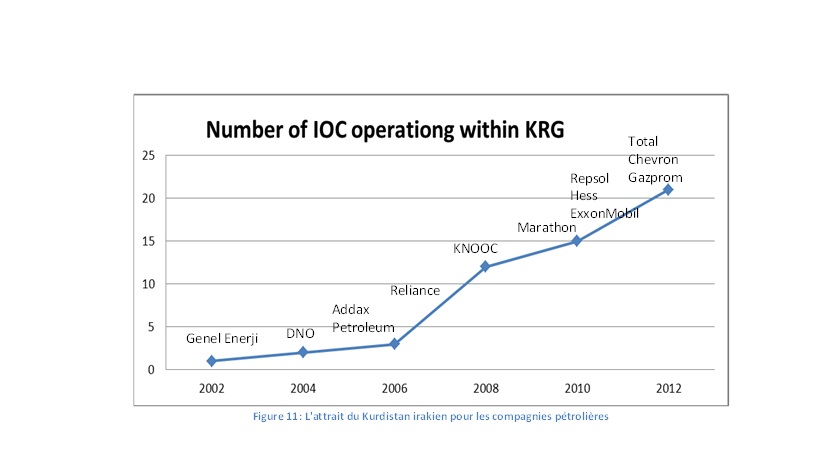

Iraqi Kurdistan has gone within a decade from an impoverished backwater to the attention grabbing frontier exploration and production region we know today.

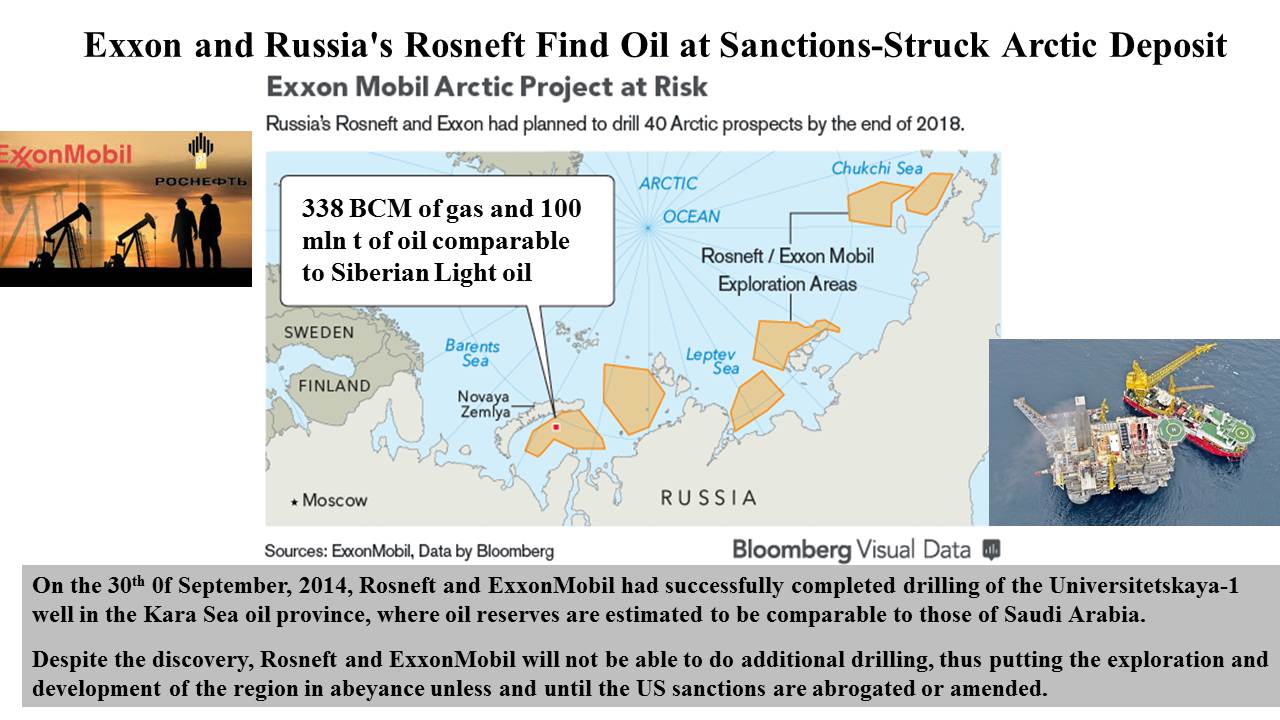

While US policy has played a major role in instilling stability and bolstering the KRG’s international profile, the emergence of the Western Zagros geological region as the most active and promising new oil basin in the world has been pivotal in turning around the economy of Iraqi Kurdistan.

Money is literally pouring into the region, whether in the form of license fees, bribes, Production Sharing Contracts, capital-intensive investments in hardware and salaries.

The fast changing face of Iraqi Kurdistan

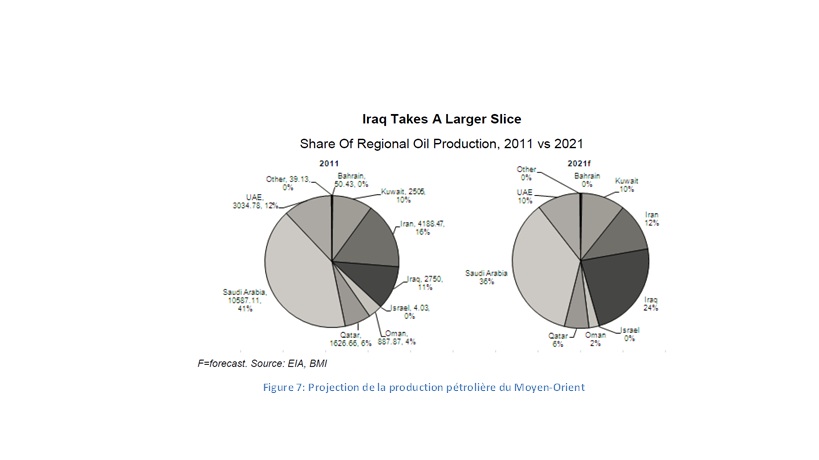

According to a paper by Azad Sadoon of Nawroz University, in 2018 nearly $108 billion of oil will be exported from the region compared to the current $10 billion per year: tenfold increase of regional income over six years.

With Kurdish oil reserves estimated at around 45 billion barrels and natural gas reserves estimated at 100 to 200 trillion cubic meters, from Erbil’s perspective, this is only the beginning of even greater things to come, as production at most fields has barely begun and the KRG output as a whole is expected to surge.

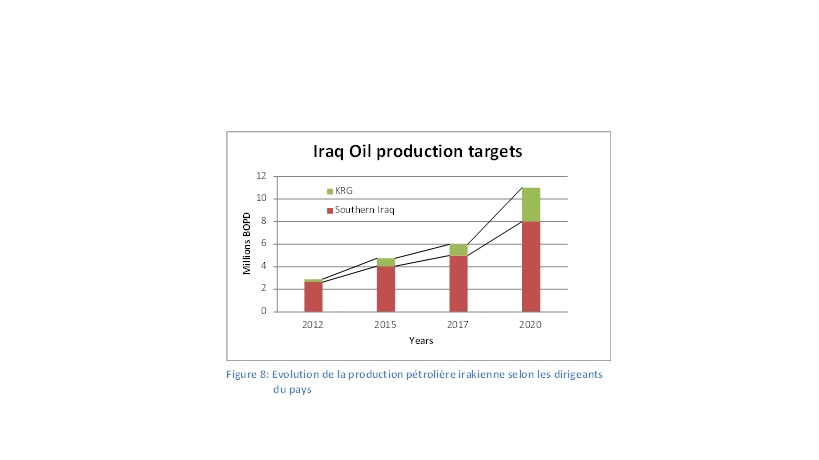

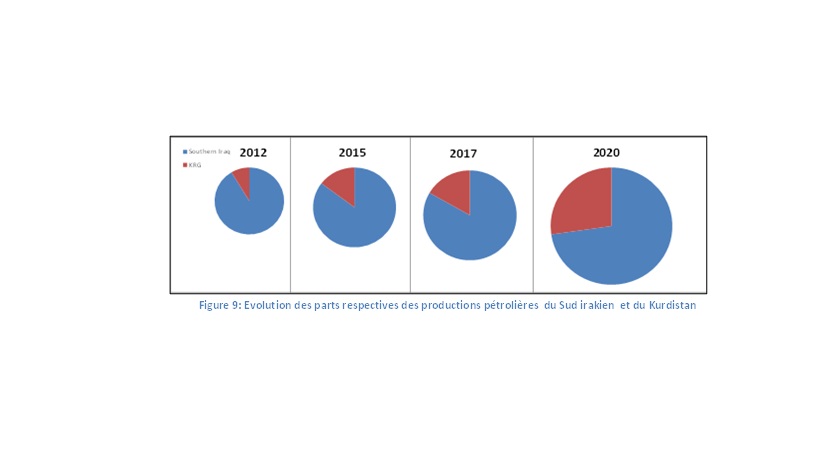

The KRG’s total production capacity is currently slightly more than 400,000 barrels per day even though analysts peg current production at 120,000 b/d. Kurdish officials say they plan to reach a production target of 2 million barrels per day by 2015, turning the Kurdistan region into a major player on the international energy map and surpassing Libya in country rankings. Not surprising when the region’s combined oil and gas reserves have been valued at 5 trillion USD.

A locked-in territory looking to evade Baghdad’s control

With the KRG at loggerheads with the central Iraqi authorities over the distribution of oil money, Erbil is well-aware that monetizing on the oil produced locally could prove problematic as exports routes are controlled by the Iraqi federal government.

In 2012, Kurdistan stopped exporting 200,000 barrels per day through Iraq’s federal pipelines and instead started trucking smaller amounts of oil to Turkey.

In keeping with its overarching aim of autonomy (some observers would suggest independence as a more truthful aim), the KRG has been intent on freeing itself of Baghdad’s dominion. This has in turn accelerated the pursuit of export routes that bypass the federal pipeline network and the search for more amenable foreign partners.

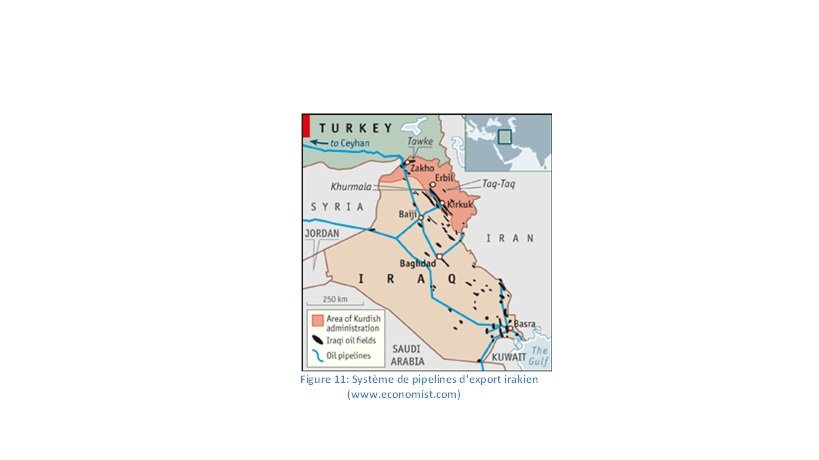

Turkey presented itself as the natural partner for the KRG. The KRG and Turkey share an extensive border and only 150 to 200 kilometers separate Turkey from Kurdistan’s oil and gas fields. Moreover, the Turkish port of Ceyhan has become an important outlet for both Caspian oil exports as well as Iraqi oil shipments from Kirkuk and is fast becoming a regional energy hub, with private investors receiving approval to build several refineries at the oil terminal.

The KRG has been intent on forging closer energy ties with their Turkish neighbor since 2012. Much of this rapprochement has been the work of the Kurdistan Regional Government’s (KRG) Minister of Natural Resources, Ashti Hawrami, who understands that it is in Iraqi Kurdistan’s interest to work with Turkey in order to eventually gain access to international energy markets and thus increase energy revenue. While Hawrami spoke out about gas exports as far back as 2012, oil has been the more actively traded energy sources, while pipeline construction has been ongoing.

Kurdish oil has already been flowing to Turkey, but flows are limited due to the necessity to truck crude to its final destination, or at least to the nearest pipeline, causing logistical issues and making the tracking the destination of the region’s oil difficult, if not virtually impossible.

Given the two-tier pricing mechanism in place which provides for steep discounts for oil sold locally (in the 50 USD/b range), the KRG has long been looking to maximize revenue by getting its oil to international markets. At present, this means exporting to Turkey and beyond.

The central piece to the KRG’s plan is the so-called Kurdish Regional Government Pipeline, which is due to connect oil fields in the northeast, KRG-controlled portion of Iraq to Turkey via an independent pipeline from the Taq Taq field (which produces about 120,000 barrels of light sweet crude per day) to the Fishkhabur node of the Kirkuk-Ceyhan pipeline. The KRG has completed the pipeline which has a capacity of 300,000 bbl/d, but Iraq’s government has threatened litigation against Turkey for buying KRG oil without Baghdad’s official approval.

A further heavy crude oil pipeline with capacity of 1 million barrels is also being built in the region.

Washington’s change of stance

A key ally of both Turkey and the KRG, Washington had long backed Baghdad on the issue of Kurdish oil exports to Turkey. The American position could be explained as an attempt to hold Iraq together along a federal model of governance that would allow for Kurdish autonomy without bringing the prospect of the country’s breakup.

The shift in US policy on the matter can be viewed as recognition of the de facto situation on the ground, as well as weaning American support for the Al-Maliki government in Baghdad.

As reported by TodayZaman, “following a meeting between Turkish Prime Minster Recep Tayyip Erdoğan and US President Barack Obama in May 2014 at the White House, US complaints concerning the pipeline have stopped”.

The Turkey-KRG energy deals

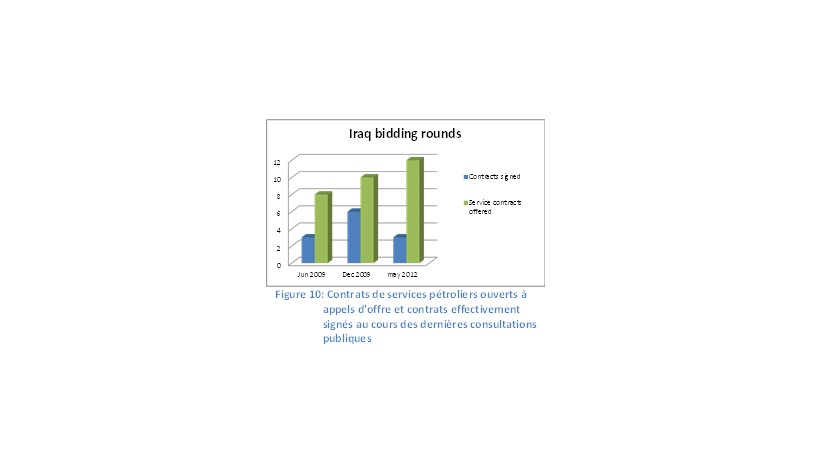

Throughout 2013 Erbil and Ankara worked on a number of energy deals. In November 2013 news broke that the KRG and Turkey signed agreements and contracts enabling Kurdish oil to flow to Turkey’s port of Ceyhan from which KRG oil exports began on May 23.

In order not to offend Baghdad neither party commented officially in the press at the time.

Baghdad opposed the agreement, claiming it would bypass the country’s national oil company SOMO (State Oil Marketing Company) and violate Iraq’s federal constitution. With everything in place prior to the lifting of US opposition to KRG exports to Turkey, Erbil and Ankara were quick to seize the opportunity offered by Washington and

The batch of deals -complemented by further agreements signed in June 2014- cover:

- The construction of a second pipeline linking Kurdish oil and gas to Turkey

- Turkish priority on oil import

- TEC assistance in handling KRG oil

- Gas imports of up to 20 bcm per year through a new pipeline, starting in 2017

- Turkish interest in 13 exploration blocks, with 6 Turkish companies granted permission to explore.

While the Kirkuk-Khurmala pipeline has captured most of the media’s attention, in part due to the controversial status of Kirkuk oil exports by the KRG, as industry sources as quick to point out “It is actually a gas game”.

Turkey’s daily gas demand stood at 125 million cubic meters in late 2012 and is likely to rise to nearly 220 million during the harsh winter months, according to energy ministry officials.

How Turkey is set to benefit from its energy ties with the KRG.

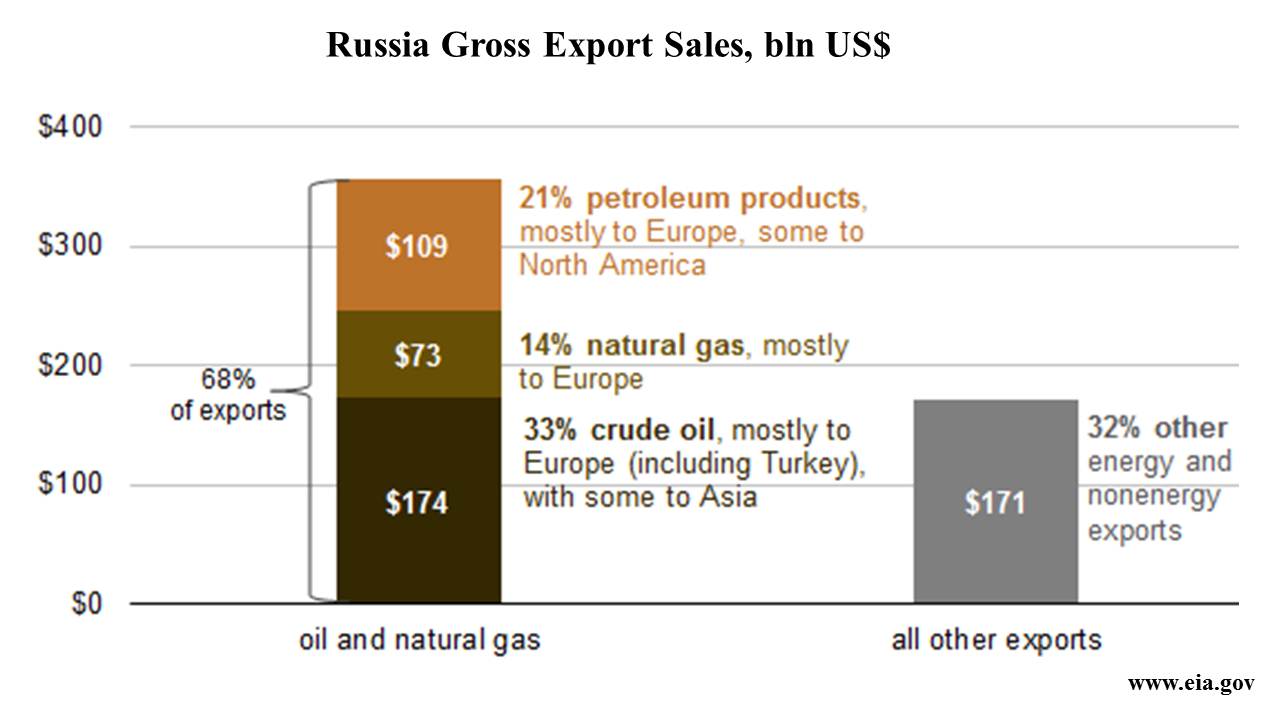

Turkey imports the vast majority of its primary energy sources, in particular when it comes to oil and natural gas.

Currently however, imports from Iraq and Iraqi Kurdistan amount to very little, with Turkey depending predominantly on Iran and Russia.

Under the agreement struck with the KRG, Ankara is set to benefit from prices on natural gas approximately 50% lower than those of existing supply agreements with Russia, Iran and Azerbaijan. In monetary terms, Ankara’s KRG natural gas imports will cost Turkey on average 200-250 USD for 1,000 cubic meters of natural gas, compared to about 450 USD per 1,000 cubic meters from existing suppliers.

Projecting the share and impact of KRG oil and gas imports

If we compare current energy demand and sources of supply to a forward-looking scenario in which Turkey achieves “energy integration” with the KRG, the significance of the new Turkey-KRG energy partnership becomes evident.

As of 2012/2013, i.e. before the energy deals, Turkish demand could be summarized as follows:

- Turkey’s total liquid fuels consumption averaged 734,800 bbl/d in 2013

- Natural gas consumption: 3 bcm (124 mcm/d) in 2012, while domestic production barely reached 0.6 bcm that year.

- Transit: four existing international pipelines with a total import capacity of some 46.6 bcm.

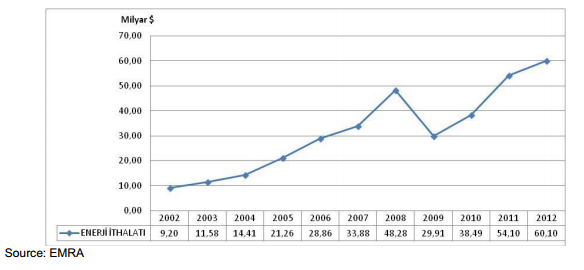

- Cost of energy imports: 60 billion USD in 2012.

Meanwhile, Turkey’s natural gas demand profile is set to turn the country into one of Europe’s largest natural gas consumer. Turkey has a number of long-term supply contracts in place and has been actively seeking additional supply partners to cover the projected shortfall in gas imports.

Russian gas is the cheapest available to Turkey, but supply constraints mean that Turkey so far has had to turn to expensive Iranian gas or to equally costly LNG imports.

In 2013 the 8 bcm of natural gas imported from the Russian Blue Stream pipeline alone were worth an estimated 3.4 billion USD.

The raft of energy agreements is set to change dramatically the outlook for KRG energy exports, with near 100% of those exports to flow to or through Turkey. The result will be that Turkey will have large volumes of available, affordable natural gas (and oil) it can import at a fraction of the price of Russian or Iranian gas.

The key aspects to bear in mind are:

- Turkey will be able to purchase up to 20 billioncubic meters per year of Kurdish gas through a new pipeline to be built via Turkey. Imports are expected to start by early 2017 even though in the IEA central scenario for Iraq (2014) natural gas exports start around 2020 with 20 Bcm/y.

- Genel Energy has stated that in next ten years, Northern Iraq may be providing 30 billion cubic meters of gas per year to Turkey.

- Kirkuk-Khurmala oil pipeline with a capacity of 1 million b/d (in addition to recent 300,000 b/d KRG oil pipeline to Turkey)

Assuming an average price of 225 USD/mcm for Kurdish gas compared to an average of 450 USD/mcm for other gas (i.e. 50% of the Kurdish price) and volumes of 20 bcm/year, then Turkey can hope to save in the range of 4,5 billion USD every year on its natural gas bill alone.

With above 30 bcm of additional natural gas demand expected by 2030, the KRG is projecting itself as the primary source of natural gas to spur Turkey’s economic growth.

The cumulative total of savings Turkey can hope to achieve by importing Kurdish gas rather than Azeri, Russian or other countries lies in part to Turkey enjoying first mover advantage as well as good political ties with Erbil. The terms of the KRG supply contracts could evolve in the long run.

State-controlled companies leading the dance

In addition, Turkey has been careful to include several state-controlled Turkish companies into the agreements with the KRG.

From oil and gas operators to banking institutions, the import of Kurdish crude is allowing Turkey to continue to develop its own energy value chain.

From oil companies to financial institutions, a number of Turkish players are set to benefit from the KRG energy partnership:

- Ankara has set up the Turkish Energy Company (TEC), a state-backed entity to enter partnership deals with Exxon and will be Turkey’s counterparty in dealings with Kurdistan.

- A dozen Turkish companies have already applied for license imports.

- Turkish TPEK (affiliated with BOTAS) is competing for the development of Kurdish natural gas fields, along with Turko-British company Genel Energy.

- Turkish state pipeline company Botas will be instrumental in building the second pipeline, which will have a capacity of at least 1 million bpd ofcrude oil, a government source said. A private Turkish company is also interested in the project.

- Despite the U.S. and Baghdad’s international pressure, as of August 2014, the KRG had managed to sell around 2 million barrels of crude oil. Payments for the tankers of Kurdish crude have reportedly been so far deposited with Turkey’s state-run Halkbank.

ERDOGAN’S RISKY REGIONAL STRATEGY

More than ever Turkey is constantly balancing risks and rewards in a volatile and fast changing region.

It is not possible to analyze Turkey’s energy supply strategy without looking at the implications of the on-going regional conflict in Syria and Iraq, along with the Kurdish question in all three countries.

Recep Erdogan has angled Turkey in such a way as to be –so far at least- the primary beneficiary of the regional chaos by both safeguarding national interest and strengthening the country’s energy supply.

Erdogan has followed a multi-stepped strategy, breaking away from past policy tenets to open up new horizons. While the initial phases have been crowned with success, the plight of the Syrian Kurdish city of Kobane, on Turkey’s doorstep, is highlighting the risks associated with Erdogan’s Great Game. International public opinion in particular has been shocked at Erdogan’s cynicism, as exemplified by numerous press articles, such as this one by The Guardian.

Not only is Turkey receiving condemnation in the world, including from its NATO ally, the United States, but its inaction has revived the deep antagonism between Turkish Kurds and the Ankara authorities, with clashes costing the lives of dozens of Turkish Kurds in early October, as reported by Amnesty International.

So how did a country go from a policy of “zero problems with our neighbors” to being mired in this decade’s worst conflict? Will Turkey go on to strengthen its position as expected, or will Erdogan’s soft spot for the Sunni jihadists backfire?

This piece aims to shed more light on this fast developing situation and its geopolitical implications for Turkey.

TURKISH KURDS

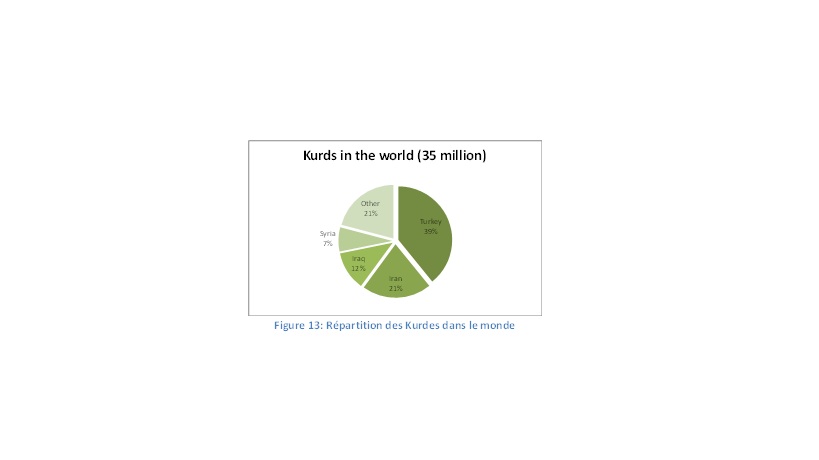

The Kurdish minority in Turkey represents 15 to 25% of the country’s total population, depending on the estimates.

Winning more of the Kurdish vote has been key to AKP victories in the latest general and presidential elections. Erdogan has been acutely aware that a first round victory in the 2014 presidential elections would require shoring up support amongst Turkey’s Kurds.

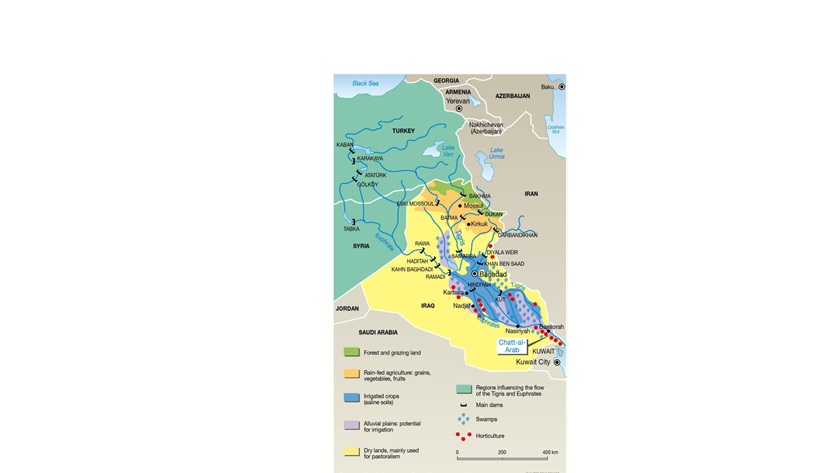

Ankara has favoured gigantic hydro and agricultural projects deep in Kurdish territory, close to the Iraqi border.

At the same time, Kurds have been ramping up pressure on Erdogan to further their own agenda. In May, the Chairman of the Human Rights Association indicated that in the past two years an estimated 2 to 3,000 young Kurds had joined PKK training camps.

Since 1984, the PKK has engaged in armed insurgency, targeting Turkish authorities, the military and energy infrastructure.

As Dr. Gönül Tol, the founding director of The Middle East Institute’s Center for Turkish Studies underlined in a piece for CNN, “the success of the Turkey-KRG energy partnership hinges on the peaceful resolution of Turkey’s Kurdish problem.”

Turkey’s strategic gas and oil pipeline system has often been attacked by PKK fighters and this in turn has meant having to buy Russian or Azeri gas at higher prices.

Erdogan’s coup de maître was to engage with the PKK’s imprisoned leader and pave the way for the watershed cease-fire agreement announced by imprisoned PKK leader Abdullah Ocalan on 21st March 2013. At the time, Ankara seemed to actively seek a long-term normalization of relations with Turkey’s large Kurdish minority.

The immediate result was the declaration by PKK commander Murat Karayilan of the withdrawal of PKK fighters stationed in Turkey.

Ankara is having to offer real advances to the country’s Kurds, while at the same time appeasing Turkish nationalists that are increasingly active since the start of the Syrian conflict.

In September 2013, a reform package was unveiled allowing the use of the Kurdish language in election campaigns, lifting restrictions on the use of the Kurdish language in private schools, abolishing the “I am a Turk” pledge of allegiance for schoolchildren and allowing Kurdish towns to use their Kurdish names.

For the Kurds, however, this was barely acceptable and the PKK warned that it may end the unilateral ceasefire. Public education in Kurdish, and the lowering of the 10 percent electoral threshold for political parties to enter Parliament remain key demands.

Unfortunately for Turkey, the government’s attitude concerning Kobane has only widened the rift between parties and Ankara is on the verge of losing the little support it had gained among Kurds since 2012. Tensions are now rife in Turkish Kurdistan, as the vocal Hüda Par Turkish political party, marked by Islamic fundamentalism and a certain proximity with ISIS, has members fighting alongside ISIS, further inflaming Kurdish opinion.

KRG

The transformation in Turkey’s approach to the Kurdish Regional Government (KRG) over the past six years or so has been remarkable. From a refusal to formally engage with Erbil and even threats to invade over perceived independence aspirations, Turkey now enjoys what leaders on both sides sometimes refer to as a ‘strategic’ relationship with the KRG and is seeking for further “economic integration”. Over half of Turkey’s considerable trade with Iraq is with the KRG and thousands of Turks reside there, with over half of the foreign companies present in the region being Turkish. In 2013, trade between the KRG and Turkey was estimated at 12 billion USD, with reports that this could double if trading conditions were improved.

KRG and Peshmerga leaders have many business ties with Turkey and have long perceived the PKK as a brake on further cross-border trade. The presence of PKK training centers and safe havens in the Khandil mountains in KRG territory has long been a thorn in relations until the Turkish AKP governing party started engaging in a political dialogue, rather than military operations. Ankara believes that greater economic ties will reduce the PKK’s funding which largely originates in smuggling goods.

Pitting the KRG against the Iraqi central government, Erdogan struck an oil import deal with the Kurdish Regional Government. This deal and rapprochement was made all the more easy since the KRG has adopted a very liberal approach under Mr Barzani, in stark contrast to the prevailing ideology amongst the PKK and amongst parts of Syria’s Kurdish minority.

Kurdistan is historically a clan-based society. Turkey knows that it risks losing the KRG’s trust if it allows ISIS to conquer any significant territory in Iraqi Kurdistan. The powerful Barzani clan is from the region of Dohuk, which has come within striking distance of ISIS troops in North Western Iraq but also borders Turkey, with many clan members on Turkey’s side of the border.

The disruptions in Eastern Iraq, combined with Baghdad’s refusal to release oil revenue and the ISIS threat to Kurdish territory has put the KRG in a weakened position and ever more reliant on Turkey as a trading partner and source of finance. If anything, the crisis has reinforced the case for closer cooperation.

IRAQ

Erdogan’s government has been paying lip service to Baghdad while promoting its own interests in the region.

Erdogan’s Turkey and Al-Maliki’s Iraq have grown more and more estranged as Iraq has turned increasingly towards Iran while a number of issues and decisions have pushed both leaders apart. Fundamentally, Erdogan has long criticized Iraqi Shia “sectarianism”.

Turkey is well aware of the outstanding issues between the KRG and the Iraqi government around the payment of oil revenues and decision-making in the Iraqi oil and gas sector. Turkey managed to overcome Baghdad main resistance when it included as part of the deal with the KRG the construction of a metering station and plans for independent auditing of oil flows from the KRG and of the management of the oil revenue from the new 1 million b/d pipeline.

At the same time, Turkey has sought to leverage its ties with the US to put pressure on the Baghdad government authorities to accept the energy deal with the KRG.

Ankara’s agreement with the KRG has elicited muted public reactions from Baghdad. Iraqi Deputy Prime Minister for Energy Hussain al-Shahristani has welcomed recent agreements between Turkey and the Iraqi Kurdish administration on oil and natural gas exports to Turkey, but was quick to add that the central government in Baghdad should not marginalized in any such agreements. Behind closed doors however, Sunni and Shia Iraqi politicians are left fuming at Erbil’s and Ankara’s decision to go it alone.

In the long-run however, with Iraqi oil production expected to climb to about 6,5 million b/d by 2035, Turkey has an interest to appease Baghdad and both countries are destined to become strong trading partners.

SYRIA

Despite its original policy of “zero problems with our neighbors”, in Syria, Turkey has chosen to support Sunni rebels in their fight against El-Assad. At the same time, Ankara has continued to withhold direct support to Syrian Kurds, in part due to the fact the Turkish government suspects the Assad regime of supporting the PKK.

Betting on Sunni insurgents to defeat Al-Assad / Ankara’s Syrian bet

Erdogan’s timid resolve to confront ISIS in Syria is in part due to the presence of an estimated 1000 Turkish nationals amongst ISIS ranks who could come back and engage in terrorist activities on Turkish soil.

ISIS has proven a magnet for new jihadists across Turkey, a reality that Ankara is have to juggle with.

At the same time, Ankara is wary of acting against ISIS as the jihadi group holds 49 Turkish diplomats captive since it conquered Mosul, Iraq’s second largest city, in June.

From the beginning of the conflict, Turkey pursued an “open-door policy” toward Syrians, and carried out successful humanitarian assistance to refugees in its camps. Turkey is appreciated for this policy and the conditions of the camps. A report published in April by the International Crisis Group described them as the “best refugee camps ever seen.”

Turkey has to deal with the 1.5 million Syrians that have sought refuge in the country, of which 200,000 from Kobane. President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan has already come out stressing that Turkey had spent $4.5 billion on Syrian refugees. Some 900,000 Syrians are registered and living in refugee camps across Turkey, while those outside camps are spread out across the country. The overwhelming majority are concentrated in five provinces adjacent to Syria: Hatay, Kilis, Gaziantep, Şanlıurfa and Mardin.

Why Erdogan mistrusts Syrian Kurds

Besides the obvious Kurdish independence fears expressed by Ankara, another, less mentioned, aspect helps explain Turkey’s reticence to allow PKK support to the Kurdish resistance factions (YPG and the PYD, the PKK’s Syrian offshoot and ally).

Syrian Turks describe their uprising in 2012 as the Rojava revolution, based on the name of the Syrian province of Rojava.

As reported by Guardian journalist David Graeber, The situation in Rojava province is in many ways reminiscent of the plight of Spanish republicans in 1936, with the wider world unaware that a democratic experiment is under threat of being stamped into the ground by ISIS.

Kobane is in fact the epicenter of the Rojava Revolution, which explains why to Syrian Kurds the fate of Kobane surpasses the strategic importance of the city’s geography and why they have appealed to Turkish Kurds to join them in defending the city.

While the Kurdish populations around Aleppo in North Western Syria and those in Eastern Syria are under the aegis of the Kurdish PYD, the city of Kobane is first and foremost been protected by the YPG

The Rojava Revolution is defined by self-governance along a participatory, decentralized model, very far from any form of centralized government structure. It borrows largely on the YPG’s political textbook.

Turkey opposes these groups not only ideologically (liberalism vs Marxism) but also politically (centralized state vs decentralized participatory democracy).

Erdogan has so far overseen a risky game of divide and conquer, instrumentalising its strategic geographical position and bouncing various factions (such as the Free Syrian Army, the PKK, the YPG and the KRG) against each other, creating a confusing landscape for many observers and indeed for Syrian Kurds themselves.

Ergogan would like the peshmerga – who are fierce enemies of the PKK – to become the vanguard against ISIS and thus undermine the PYD/PKK alliance.

If anything, Kobane is now rather left to its own devices, until Erdogan or Barzani (the only 2 regional players with political clout backed by operational troops) decide to achieve reputational gains.

As the Asia Times Online Editor-in-Chief puts it in his “The Kobani riddle” article dated 24th October, “the barbarians, in the form of Islamic State goons, are at the gates of Kobani, the (…) epicenter of a non-violent experiment in local democracy. But don’t expect the US, Turkey and the administration of Iraqi Kurdistan to save Kobani (…). None of these actors want the direct democracy experiment in Kobani and Rojava to bloom, expand and start to be noticed all across the Global South.”

Turkey is bent on ensuring the permanency of the current regional borders and fears above all a resurgence of Kurdish national aspirations, which could potentially lead to a redrawing of Turkey’s eastern borders.

Therefore it is in Turkey’s interest to displace Kurdish populations currently living in Northern Syria along the Turkish border. The further East the Kurds resettle in Syria, the lower the risk to Turkish borders. Eventually, a much reduced Syrian Kurdistan could only seek to (a) remain as a part of a federal Syria or (b) breakaway to join the KRG, thereby redrawing the boundaries of Iraq and Syria. At this stage, both these options appear as distant possibilities at best.

Syria in the regional energy equation

As a result of the turmoil and ISIS capture of the country’s main oil fields and despite Syria’s drop in production, more discounted oil is reaching Turkey than ever before. It is estimated that as of January 2014, Syria’s total daily oil production had fallen from 300,000 b/d down to 25,000 b/d.

Depending on sources, ISIS now makes a profit estimated at between 1 million USD and 2 million USD every day from oil taken from the Rumeilan region in Eastern Syria, where 2,000 wells and refineries have fallen under ISIS’s sway. The largest Syrian field, the El-Oman has been under ISIS control since June and ISIS continues to this day to attack the remaining oil and gas assets in Syria.

This has often resulted in direct armed confrontation against Jabhat al-Nusra and Kurdish YPG protection units in Rojava, each group vying for control over the revenues from the sale of petroleum products to Turkey, in particular the stretch between the districts of Cizre in Sirnak province and Nusaybin in Mardin province.

The crude, often stolen directly at refineries, is exported mainly to Turkey, but also to Jordan and Iraqi Kurdistan at discounted prices, with reports of jihadists making a little over 20 USD per barrel. Turkish and Kurdish authorities have rebuked these claims. Nevertheless, a Turkish official from the border region of Hatay claimed in June that as much as 800 million USD worth of oil has already been smuggled into Turkey. Turkish newspapers reported that “the daily amount of smuggled diesel fuel (from Syria) had reached 1,500 tons, which corresponds to 3.5% of Turkey’s consumption.”

Smuggling of various qualities of oil and petroleum products is now done through pipes from villages near the Turkish border at Hatay but also Kilis, Urfa and Gaziantep, after which they enter the international oil circuits.

This new source of cheap oil has added to the drop in global oil prices.

Saudi Arabia has taken the lead in a bid from Sunni Arab countries to flood the market with cheap oil as a way of punishing Russia for its support to Damascus and in order to stave investments away from shale and ultra-deep plays that could capture increasing market share. Reuters has reported on 13th October that Saudi officials have hinted at prices in the 80-90 USD per barrel for the next year or two.

Ultimately, those benefiting have been the consumer nations worldwide and, first and foremost amongst these, Turkey.

CONCLUSION

So far then Turkey has managed to maintain its position within suffering no more than limited domestic unrest and international criticism. Still, the PKK ceasefire still holds, relations with the KRG leadership remain excellent, the Syrian Kurdish “Rojava Revolution” is a fast diminishing political alternative, which reduces the likelihood of having to redraw the country’s southern border and Turkey is enjoying greater flows of low cost imported oil from its immediate neighbors.

While we are nowhere near the end of the Iraqi-Syrian conflict, and Turkey has had to recalibrate its foreign policy several times since 2012, but Erdogan has so far played his own version of the Great Game to great success, despite the perils.

Moving forward, one can expect Turkey to continue to cherish its partnership with the KRG. Ankara will do everything it can to secure its slice of Kurdistan’s economic miracle.

Author biography

Thomas Esdaile-Bouquet is an international energy affairs expert, having worked on sustainable energy, oil and gas and climate policies and markets for the past 10 years.

An alumni of both the Strasbourg and Bordeaux Institutes for Political Sciences, Thomas has held positions in Washington, Paris, Brussels, London and Geneva, advising consultancies, industry trade associations, UN agencies, ministries and multinationals. He is currently based in Switzerland.

This piece is written in his personal capacity and the views reflected are his own.

Follow Thomas on Twitter: @tomesdaile